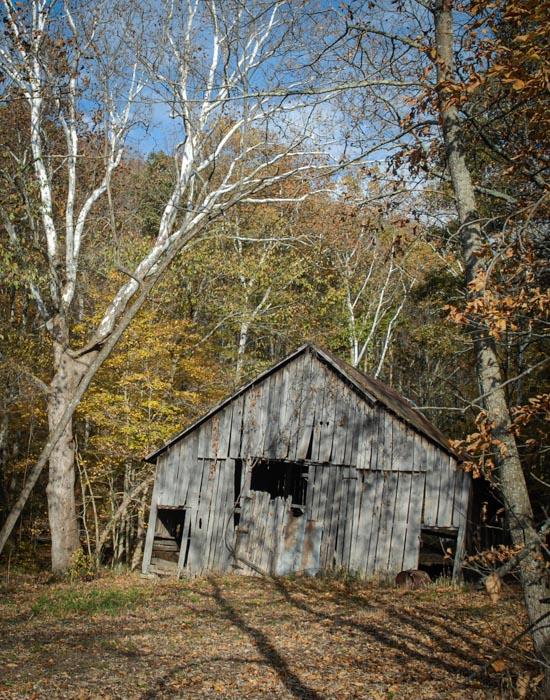

What is the fascination with old bucolic barns? I don’t have a clear answer, but catching sight of weathered barns, sheds, or other similar old and sometimes dilapidated relics grabs my attention. Perhaps, it is because barns are a symbol of hard work, integrity, and the American dream. Or it could be that they represent our rich agricultural heritage—for a lifestyle that has all but disappeared. They were built in a time when there were no cell phones, video games, or television sets. The telephone was a party line. It was a time when the entire family worked as a team. Rural families baked their own bread, canned vegetables, and put the laundry out on the line to dry. Fathers worked hard around the farm all day, and so did their children. It’s a story of hard work, self-reliance, and family.

Water stained, windblown, and sun-bleached barns can remind us of days gone by when life was simpler and work was more physically demanding. They speak to us of another time, old crafts, and perhaps even significant historical individuals. Old barns and abandoned buildings may ferment our nostalgia for an idealized past. Old barns also have a romantic dimension. They can evoke literary and emotional associations:

- “you weren’t born in a barn”

- “daddy’s gonna skin your hide and nail it to the barn door”

- “it’s no use closing the barn door after the horse has bolted”

- “as broad as a barn door”

- “It’s a real barnburner” or

- “can’t hit the broad side of a barn.”

Perhaps the attraction with barns is the mystery of what is behind doors that have been locked and abandoned for decades. If barns could talk, what stories would they tell us? Who labored to construct the barn? What conversations took place in them? If only we could hear the whisper of ghosts in these rustic barns and the stories they could tell of the vibrant past.

Perhaps the attraction with barns is the mystery of what is behind doors that have been locked and abandoned for decades. If barns could talk, what stories would they tell us? Who labored to construct the barn? What conversations took place in them? If only we could hear the whisper of ghosts in these rustic barns and the stories they could tell of the vibrant past.

Preserving barns are a way to preserve America’s agricultural legacy. Many picturesque barns are irreplaceable. They’re also historical. If rustic barns really touch us deeply and viscerally, then why are so many neglected? Many barns are disintegrating as a result of inattentive maintenance. Many are literally falling down, and their roofs collapsed, too old to store anything in. Over the decades, other barns have been destroyed by wind or fires. Countless picturesque barns are no longer structurally sound. Their bones are exposed to the elements—old lumber slowly rotting away.

My great grandfather homesteaded a farm in Guthrie County, Iowa. As I was growing up, my uncle farmed the land. Cattle, hogs, and chickens were raised on the farm. They grew corn, beans, and baled hay. I have fond memories of visiting the family farm as a child. The barn was a shadowy world of churning dust illuminated by the stripes of light shining through the cracks in the old boards. A creaky windmill pumped water into a trough. A communal metal cup that hung next to the cast iron hand-pump. We could frolic in the barn and build tunnels with the hay bales. The smell of dust and hay hung in the air. It was also fun to jump and play in the bin of shelled corn.

Barns were essential to early farmers. They protected farm animals and stored crops. Without them, farmers couldn’t survive. Barns were about usefulness and economics—not style—they were utilitarian. The barns had logical simplicity. “You see where hay was loaded in, stored, moved to the animals.”

Barns were constructed for specific purposes. The style and design would change, depending on its use for dairy, grains, fruit, poultry, tobacco. New farm buildings are changing as farming continues to change.

Over time, styles and construction material, and building techniques changed. This included orientation to the sun and the prevailing winds. It also included accessibility and efficiency.

Economically viable farms are much larger now than they use to be. With the use of huge equipment, one farmer can farm many more acres. This is displacing many smaller farms. Rural populations are decreasing as people move to towns and cities to find work. The historic and wonderfully aged structures are no longer needed as multiple farms are condensed (collected) into one. With today’s mechanized agriculture, modern machinery may not fit into the historic barns built in a time of horse power.

Braced frame construction is the most common style of American barns. Air could circulate through the cracks between boards. Large doors provided good light. Shed-roof additions could be added on the side or back of the barns. Adding additional stories provided more space on the same-size foundation and roof. Access to the barn was improved if the barn was located on a hillside, allowing the farmer to enter at several levels. Doors at opposite ends provided good cross-ventilation and allowed wagons to drive through. Rows of windows were a way of letting in more light.

Hoists, ramps, chutes, and sliding doors provided ways to move materials through the barn. A louvered cupola increased ventilation. Butch barn and Bale Doors were practical. The bottom door keeps the animals in or out of the barn. The top door allows for ventilation, light, and socialization.

Gabled roofs were most common with American barns because of its simple design and the roof timbers’ regular shape. A gambrel roof has two slopes on each side. This provides more usable space overhead. The upper slop is position at a shallow angle, and the lower lop is at a steeper angle.

Round barns have never been as common as quadrilateral shaped designs. They get more attention because of their unique shape.

Weathered round barn

Round barns were intended to improve efficiency and provide maximum ventilation. It was believed that round barns were sturdier and could better withstand severe weather.

The paint was used to protect the wood from the elements. Farmers made their own paint. Typically, this included linseed oil, skimmed milk, lime, and red ferrous oxide earth pigments. The red ferrous oxide, which created the red barn color, protected the wood from mold and moss, which caused decay. The fungi would trap moisture in the wood, increasing decay. The paint mixture created a red-tinted plastic-like coating that hardened quickly and lasted for years. Linseed oil improved the soaking quality.

Light is essential to every photograph. Light can add drama, obscure details, or create flattering lines. Capturing an image with impact means finding the right light, whether before a gathering storm, a nighttime long exposure, or a moody silhouette.

Some of the best photographs of barns were taken near to sunrise or sunset when the angle of light is low and warm light washes over the landscape. Fog and mist soften and mute colors, but they add mood, atmosphere, and even mystery. Converting an image to black and white may add power to an image and set it apart from other images. Don’t be afraid to step back from the building. Including surrounding objects like old farm equipment or trees can help to tell the story of the barn. A polarizing filter will provide more saturated colors. A polarizer will also provide better separation between the clouds and the sky.

You may not notice camera shake with small images, but it can become glaring with large prints. To avoid motion blur, I use a tripod when photographing most scenes. This also gives me more control over the depth of field. Reduce sensor noise with a low ISO, made possible with the use of a tripod.

Taking a snapshot of a barn is easy, but for fine art architectural photography, you need to capture the building’s essence. This may require pre-planning, the best light, proper equipment, a compositional strategy, and editing techniques. Take your time when photographing historic barns. Your image will be more creative and of higher quality if you analyze the scene. You might discover different angles or focus on a particular detail. The historic barns have been in that location for many generations, and they are not going to run away from you.

0 Comments